By Deb Peterson

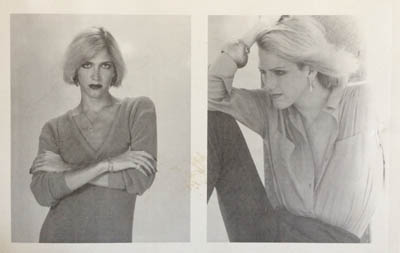

When you see Madeleine Litton across a room for the very first time, you can’t stop looking at her. Not because she’s an inch shy of six feet. Not because she’s as stunningly handsome as she is beautiful. Not even because she’s always meticulously dressed and bejeweled. You can’t stop looking at her because she exudes marvelosity, a word she made up while joking around (not about herself). It’s a word that perfectly describes her energy.

She’s worked hard for her marvelosity. Madeleine is a person who says yes to life, to happiness, to learning new things. That sounds fun, and it is, but it’s also a very proactive way to live. It requires awareness and introspection, conscious decision making, action. It takes courage—the courage to be independent, to be willing to change, to start again. And again. Some people might see this as fickle. I see people like Madeleine as brave.

Madeleine has walked runways as Olivia Brooks wearing Oscar de la Renta bridal gowns, sold real estate in Virginia horse country, earned certificates in gemology and interior design, degrees in Spanish, history, and education, volunteered on the successful campaign of now Chief Justice Sandee Bryan Marion of the Fourth Court of Appeals in Texas, and taught high-school Spanish in San Antonio. She is now painting canvases people want to buy. She has so many diplomas and certifications that I became a little skeptical. Really? Really. She spread them all out on her bed for me.

When Madeleine’s life changes in a way she doesn’t like, she pivots right along with it. She takes charge of whatever she can. She goes back to school and learns something new. A dentist friend once put things in perspective for Madeleine when she was contemplating a new career and wondering about taking the time to go back to school.

“You take out a ruler and take eight inches,” Madeleine remembers her friend saying. “Each inch is 10 years of your life. Four little millimeters represent going back to school. That little bit of training can make all the difference in your life. So every time I retrain, it’s not that big of a deal.”

Madeleine’s parents emphasized education and exposed Madeleine and her sister, Connie, to the big wide world around them. Her father, James Loeber, an attorney and business department chair at Florida State University, died shortly after rocking 4-year-old Madeleine to sleep one evening. He was only 46. Madeleine’s mother, Myrtle, remained single for 18 years, working in insurance and raising her daughters to be strong and independent. She frequently took them to museums.

“We were constantly bombarded by art,” Madeleine remembers. “Mother exposed us to everything she could.”

When Madeleine was 12, her mother sent her to the Galapagos Islands with Dr. Frances Nimko, a social anthropologist and family friend, to participate in a scientific expedition. Madeleine sat next to sea lions and marine iguanas, and the experience awakened in her a passion for travel and the welfare of animals.

“It was just like seeing one of those IMAX movies,” Madeleiene remembers. “That’s really and truly what it’s like. The animals had no fear of us because they hadn’t yet learned to fear us.”

At 15, she was off to boarding school at Durham School in England (where parts of Harry Potter were filmed) for her junior year of high school, a part of the American Institute for Foreign Study. There, she met kids from all over the world.

“It taught me a lot about what other people thought about the United States,” she says. It was the early 70s.

She was ready to graduate at 16, but Mother said no. By the time Madeleine was 17, she was so bored with school she started modeling as a live mannequin in Tallahassee boutiques. It was likely the last time she stood still. Myrtle wasn’t thrilled with the idea. She wanted her daughter to finish school and find a solid career.

Madeleine tried. She enrolled in the zoology program at Florida State University with her best friend since fourth grade, Deborah Maloy.

“We have a lot in common—music, fashion, an amazing love for animals,” Deborah says. “We were both misfits. Not the most popular or athletic or pretty. We kind of saw ourselves in each other and we still do.”

“I was shy and scared, and such a big geek,” Madeleine remembers about her childhood.

Deborah finished her degree and went on to work with wildlife and in zoo medicine. She was recruited by a sanctuary to help save circus elephants from tuberculosis. In August, she will teach veterinary nursing at Texas A&M.

Madeleine lasted three semesters before losing her academic scholarship because she was more focused on modeling. Myrtle was still against the idea.

“My mother said, ‘No, you’ll starve to death,’” Madeleine remembers. But Myrtle had done her job well, instilling in her daughter a fierce independence, and Madeleine had her mind set on modeling. She had modeled for Spiegel catalog but, she says, she wasn’t very photogenic. She was tall enough for runway work and she was getting noticed. A photographer called and wanted to see “her book.” It turned out that wasn’t all he wanted to see. Madeleine was 21 and gaining wisdom fast.

When she got the big call from David Christensen, a photographer in New York City, she was married and living in Virginia. It was the beginning of her runway career.

“Runway modeling is all about legs, legs, legs,” Madeleine says. She was 5’11”. “I had a bone curvature in my left foot that I got from my dad. Because of that, Mom put me in dance class, so I knew how to walk.”

She could model for an hour and a half, and make $250. It was 1981. The cost of an apartment in New York City was high, so Madeleine stayed in Virginia and traveled to her shows. For three plus years she worked the runway, especially bridal shows. The top model in the show opens and closes the runway. That was usually Madeleine. She socked her money away in a savings account.

Myrtle may have been a little surprised. “She was very unaffected by it,” she says of her daughter. “She didn’t change at all.”

That wasn’t without Myrtle’s influence. She can remember fixing a big meal when Madeleine came home for a visit. When Madeleine left the table, Myrtle was suspicious and followed her daughter to the bathroom. She stood outside the door and said, “Don’t you dare throw up my food.” And that was the end of that.

“Myrtle demands your best,” Deborah says. “She’s my second mom. She sets high standards. She expects to be treated well and anything less is unacceptable. She wants the best, for people and for animals.”

By the time Madeleine was 27, she learned that her mother was right. One day she arrived for a runway show and wondered why there was no bridal gown hanging on her rack.

“They told me I was modeling second wedding and mother of the bride,” Madeleine says with a wry expression. “I knew it was over.”

While her runway career was fleeting in the grand scheme of life (she knew it would be), the runway would prove to be a fitting analogy for the turns her life would take over the next 30 years. When one “show” ended, Madeleine outfitted herself anew and walked down a new runway as she searched for the life she wanted. The value of school was also becoming evident to her. Each time life changed, she chose a new direction, learned what she need to know, earned the degree or certification she needed, and found her way.

She got her real estate license in Virginia and sold a grand total of three properties. “I hated it with a passion unbridled,” she says.

She went to the Gemological Institute of America in Lawton, Oklahoma and became a gemologist, working for Macy’s and Burlington Coat Factory, and she hated that, too. “I was bored out of my mind,” she says.

She moved to Texas, worked in politics for a while, and got certified in residential design and space planning. It was the early 90s and there were no jobs, so it was back to school again for Madeleine. She earned bachelor’s degrees in business and Spanish. She modeled for charity. She traveled to Spain and Mexico to improve her Spanish. Myrtle said, “Why don’t you teach?”

She tried subbing to see if she would like teaching, and she did. She earned an education degree with a history discipline. She was 42 and living in San Antonio, and there she found her next runway, one that would be 14 years long.

The North East Independent School District in which Madeleine taught invites each senior graduating Summa Cum Laude to an annual reception where they are honored individually on stage. Each student chooses one educator they want to recognize with a short tribute for having had the most positive impact on their lives and education. Madeleine has received this commendation eight times! She was first chosen during her fourth year of teaching, and returned to Churchill High School last year, after retiring, when she was chosen by three students.

“It’s a wonderful honor coming from a teenager,” Madeleine says. “Some of them I taught in their freshman year! It truly made the decision to teach worth it. The kids mean everything. Their opinions aren’t jaded. Politics aren’t encumbering their choices. It is the applause teachers rarely get.”

Her retirement from teaching came early when husband Brian Litton was promoted in the petroleum industry and transferred from San Antonio to Midland. The couple had visited Aunt Laverne, Myrtle’s sister, in Mountain Home in the past, and Madeleine remembered how pretty it is here.

“We came for a visit and Brian loved it,” Madeleine says. “I had always wanted a log cabin and a river. I like water that moves. I want a fresh supply. I don’t want to be on the water. I just want to see it.”

They bought a “tired, sad little place” on 32 wooded acres and spent two years renovating it as a vacation home. Madeleine wasn’t moving to Midland. One and a half years ago, on Myrtle’s 93rd birthday, Madeleine and Myrtle moved into the log cabin. Brian comes every chance he can get. Madeleine wasn’t entirely sure what to do with herself. It was time to find a new runway. She got busy meeting people, making friends, and volunteering.

“Don’t stay at home,” she advises people who want a change in life. “Nobody’s going to knock on your door. You have to be out there. That’s how you meet people. Volunteer.”

Brian said, “You’re retired. Why don’t you do something fun?”

“I didn’t even know what that would be,” Madeleine says. She heard about Painting with Panache at Big Creek Golf & Country Club with Jim Tindall and Lucinda Blair. She signed up, and she loved it. She hasn’t stopped painting since. She, Barbie Graham, and Toni Olden now take weekly private lessons from Jim, and Madeleine has started selling her work. She put photos of her paintings on her Words with Friends profile, and her friends wanted to buy them. You can see some of her work at Simply Beautiful in Gassville.

Her art is especially beautiful when you consider that Madeleine is legally blind. She has a cataract growing slowly in one eye. She has a vent in her right eye where the retina pulled away but didn’t tear. She says it’s like someone smeared Vaseline across your glasses. She has something called a lattice, which she says is not uncommon in people with astigmatism. Her pupils don’t regulate light properly, so she is very sensitive to bright sun, and she doesn’t drive well at night. She has had laser repair once, and had her eye makeup tattooed, and she doesn’t let the situation get her down.

“Both eyes are heavily nearsighted and misshapen,” she says. “Christmas trees are incredibly beautiful through my eyes! I really can’t see a thing without correction. There are so many people with far worse vision than mine. I am lucky!”

She often paints without correction, seeing only the value of the colors Jim wants her to use. Then she uses glasses or contacts to detail her work.

Her animals don’t care at all that she doesn’t see them well. Her eyesight has no impact at all on the care she lavishes upon her five dogs, five ferrets (she calls them weasels), three cats, and two fish—all rescues.

“She has a huge, huge heart,” says friend Cynthia Dalrymple. She calls Madeleine Olivia. “She is generous not only with animals, but with people, too.”

The two were neighbors in Texas. When Cynthia came to visit, she and her mother, Virginia, who was Myrtle’s walking partner in San Antonio, followed Madeleine and Myrtle here. “Olivia opened my eyes to Mountain Home,” Cynthia says.

It isn’t surprising to me that Cynthia chose to follow Madeleine to Mountain Home, or that Madeleine is still close to Deborah.

Madeleine’s triumphs over life’s inevitable struggles are inspiring, her marvelosity endearing. People are drawn to her.

“Even though I look at Madeleine now and think she has had it all, it hasn’t been without pain,” Deborah says. “She has struggled to find her place in the world.”

“I’ve done everything I’ve ever wanted to do,” Madeleine says. “I don’t want to get to the end of my life and say, ‘Oh damn, if I had only done that.’ If you have the money, do it.”

“She’s been fortunate,” Deborah says. “She’s brilliant. She can set one life down and pick another up, but it hasn’t been a breeze all the time. She’s done the work. She searched. It’s becoming easier because she believes in the person she has built.”

We are fortuntate, too, that Madeleine Litton is now sharing her marvelosity with us, and teaching us all how to pivot through life. M! June/July 2016

Madeleine’s struggles have made her wise in addition to marvelous, and she’s willing to share her wisdom

• It’s very important for women to have their own money and career. It gives them their own identity and a feeling of self worth. If you don’t have that, no matter what changes you make, you’ll never be satisfied or fulfilled. Because I had that, I could go on when life fell apart.

• When life isn’t working, keep at it while you work on changing it. It’s your decision. Nobody can tell you when or how to change.

There is a lot of stuff in life that sucks. So you better step out and do it, go out on a limb. Those are the things I learn the most from.

• It’s very important that the career you choose is one you enjoy. Ask yourself, can I do this for a long, long time? And then don’t be afraid to learn something else if it turns out to be the wrong thing.

• Listen to Myrtle: You’re not better than anyone else, and you’re not worse than anyone else. You’re as good as anyone else and you can do anything you put your mind to.

• Even if it’s in your nature to think of all the things that could go wrong, overcome the fear and keep going. It’s the only way you have fun. It’s the only way you discover!

Leave a Reply