By NEIL CHANDLER | Photos courtesy of Neil Chandler

When I watch a bird, pet an animal, touch a tree, follow Orion’s march across the southern sky, or wind that old Seth Thomas clock each evening, she lives.

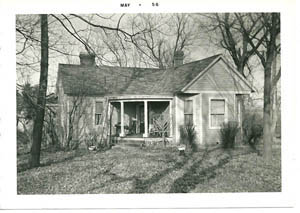

Born in the 19th century, Maud Taylor Chandler lived far into her 10th decade. I neared middle age when she died but my tears still flowed, a wrenching sadness similar to the feelings I suffered when leaving her after each blissful summer vacation on her idle farm during my childhood years. The Missouri farm had been anything but idle during most of her life; she and my grandfather produced much from the hilly 120 acres, including three sons, one lost at birth. After her husband died she continued to live alone for a quarter-century in the small, comfortable house they built together after the boys were born.

It was their second home, identical in all respects to the first that burned before either son had yet attended his first formal classroom. While my grandfather pumped water from the porch cistern to fight a lost battle, Grannie herded her brood to safety across a gravel lane some 30 yards away. She returned and snatched from the flames a few small items, including a camphor bottle that accompanied our family’s first arrival from Ireland in 1760, and a later acquired 1840 Seth Thomas mantle clock. Those two relics sit in my living room, the rest now scattered among other family members, but I don’t need to study or hold my treasures to re-live my time with Grannie.

I don’t remember my first hours near her; the last hold clear, but that will come later. In fact, time with my grandfather fills most of the early memories. During long summer days, Pa and I fed chickens, milked cows, repaired harness, plowed fields, and ground livestock feed. I usually accompanied my father when he made the fall trip to help strip corn from the stalks Pa had tended since late spring. It seemed the two kept an unending drumming of ears against the sideboard of the wooden wagon. I walked behind with instructions to pick up any missed tosses. I had little work, and back there I was out of the workers’ way. Though not specifically suggested, I learned that harvest rewards came from tilling, planting, and cultivating along with adequate prayer for rain.

Coal oil lamps splashed flickering light on Grannie as she slumped across her husband’s casket in the little-used parlor of their home. She cried, and that action puzzled me, for until then I considered her dispassionate in all activities. Yet I knew she loved because she clung hard to her sons. Her second son, my uncle, sporadically lived at the homestead during job-famine depression years, and I overheard stories of Grannie driving off several suitable mates.

When my father married at age 25, Grannie refused to attend his wedding and spent the afternoon cutting underbrush in a little-used area of the farm. I wonder how often my mother held her temper until grandchildren arrived and softened the relationship with her mother-in-law.

Many things changed for Grannie after Pa died, but my summer vacations with her continued until mid-teen activities pulled me away and visits shortened. Those lengthy times became periods of learning; now my time was with her alone, not shared with another grandparent. Cows and horses were gone but chickens remained. I helped her with chores, although little was required. I pumped water and wheeled it to the pens in Pa’s improvised tanker. The brood ate cracked corn we hauled from the barn. She tolerated the resident mice-eating black snake; I feared it.

She reserved the mid-day for informal (and my unwitting) instruction. Family history, both hers and Pa’s, rolled endlessly from her memory. The late 19th and early 20th centuries became more than history as we explored it together. She easily offset hard times, hard labor, and little money with the peace derived from independence, solitude, and respect for all nature. I learned of birds, beasts, plants, and trees. When the day’s heat dissipated, we sat outside on steps leading westward, observing all and talking. The lot across the drive contained nearly every species of tree common to that area—trees she and Pa had planted and nurtured from the time they first came to their land. She identified each for me and drilled me on my retention. Within a couple of yards from where we sat, birds came to eat at the window feeder she filled year round, and she expected me to name each. I listened and learned even though passing years have robbed me of great portions of her teaching. After dark, the night sky became a classroom. Again, I studied, watched, and stored away shapes and positions of constellations.

She listened each summer to my stories of mice scampering nightly in the walls near my bed on the screened porch. I declined her offer to bring the barn snake to the house. Her deep love of nature and all creatures could not be taught or accepted when it came to snakes; they still cause shivers when met unexpectedly. But with a jar of succotash for lunch and dog-companion Tiger, my explorations of valleys, creeks, and forests over each hill received her full encouragement. I continued those adventures, even knowing I would be quizzed on each discovery, whether new or replicated. I dared not, nor wished to, withhold the adventures.

I never wanted to leave her, but school and life called. Long Christmas evenings and holidays lounging in front of her fireplace ceased, replaced with hurried one-day visits. College came and went and obligatory military service ensued. One cold Christmas evening, I dressed in civilian clothes and bundled my parents into my auto, stored a scraggly evergreen in the trunk, and drove three snowy hours to the familiar farm. We brought food, but she would not let us eat until she added red-eye gravy to our meal. Oh, she could cook. Even though surprised by our visit, her dark pantry contained a heavy, yellow cake with chocolate icing. I cannot recall a time when her cupboard was bare.

I sat nearby her hospital bed before she underwent gall bladder surgery. She neared age 85 and doctors expressed concern, for at that time the operation required significant surgery, stitching, and anesthesia. She told me not to worry as she still had a few things left to do. I don’t know if she accomplished those wishes in the next few years, but I’m certain she tried.

Yet finally the time came when she left her home and moved to a place where someone provided help. She did not handle her loss of independence well, and her mental and physical deterioration began the day she locked the door of the house where she had lived for three-quarters of a century. She still gripped my hand when I visited, but I never felt convinced that my grandmother looked through those familiar gray-green eyes that welled tears.

My tears flowed as I listened to the eulogy. The minister tried, but no outsider could adequately sum up her life. I couldn’t fully explain my loss then, and I can’t today, but when I watch a bird, pet an animal, touch a tree, follow Orion’s march across the southern sky, or wind that old Seth Thomas clock each evening, she lives. That’s the sum of it. M! August/September 2014

Leave a Reply